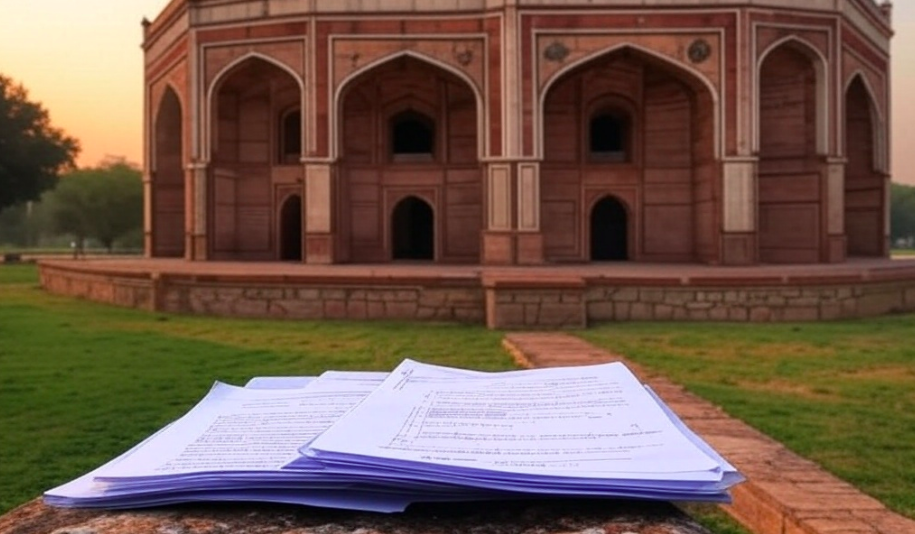

World Heritage Day Spotlight: Waqf Relics in Delhi Caught in Crossfire

At least 156 historic sites, many dating back to the Mughal era,…

India’s Oldest Surviving Islamic Palace in Danger

SM Fasiullah for Beyondheadlines Lal Mahal, an oldest surviving Islamic palace in…