Aakshi Magazine

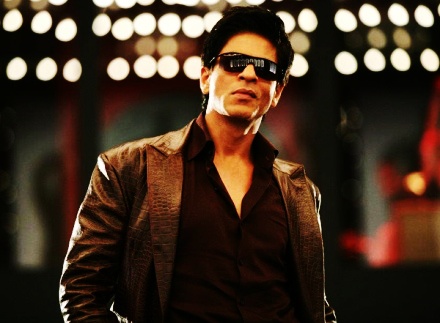

‘Shahrukh has always told me that physical abuse is the worst way to sort out a problem, and that it means the person who’s hitting has either a personal or professional crisis going on. So it saddens me to see him doing the same.’ -Farah Khan, Mumbai Jan 30, 2012.

The lover boy of mushy Karan Johar movies seems to be becoming desperate. He resurrected himself as a larger-than-life action hero in Ra.One.

The Rs 150 crore film was a super duper disaster, despite the last minute Rs 50 crore marketing promo blitzkrieg. Clearly, ageing superstar Shahrukh Khan, on whom billions ride in Bollywood, is beginning to get stuck in his own repetitive mediocrity.

Towards the end of Ra.One, there is a scene in which Shahrukh is dying: he resorts to a gesture fans recognise too well from his romantic films – arms stretched, eyes crinkled, head raised. At a screening, some people started laughing” “Can a Shahrukh movie be complete without this,” they said. This moment must come in every star’s life when they start appearing as caricatures of their own manufactured self-image. What was liked once, now begins to be made fun of. Recently, Naseeruddin Shah, great actor but not a star in Bollywood language, remarked that “big stars have to be predictable”. That seems to be both their doing as well as undoing.

All his life, Shahrukh has played different versions of only two roles – the too-much-in-love lover, and the ordinary simpleton bordering on being a buffoon. With changing times, these characters too changed – getting tamed, altered, commercialised.

For those of us who grew up on mid-1990s Bombay movies, Shahrukh was fundamentally Dilwale Dulhania Le Jaayenge’s (DDLJ) Raj, or Kuch Kuch Hota Hai’s (KKHH) Rahul. He seemed attractive, almost charming; there was something about him, what, exactly, we could never say.

Prosperous Raj and Rahul were eternally well-settled with not the slightest worry about how to make a living. Their world and worries merely revolved around finding ‘love’. They were irreverent, but not far-sighted or courageous enough to question basic conventions and traditions. They were mostly happy till love made them sad, though never angry; even that sadness never lasted.

However, the Shahrukh we did not know, occasional glimpses of whom we saw in older movies on TV, had also been other people. Look at the first two films of his career, in theearly 1990s. He was the crazed lover Raja in Deewana, ready to defy social convention for love; also, Raju in Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, wanting to become a gentleman in the big, bad city.

Raja and Raju were interesting. In many ways, Raja is an early version of Raj and Rahul. Like them, he is rich and happy. But these are slightly different times and so, unlike them, he is angry at his wealth, at his father, who, for him, is the symbol of this inherited wealth: “Maine toh yeh nahi maanga tha,” he tells him.

Raja was a heavily ‘overacted’ but interesting character who falls in love with a widow. Not caring for a thing in the world (not even for what the woman feels!), he decides to give up family wealth and works in a garage. There was a mad energy about him, as if he did not know what to do with the emotions evoked inside him. In a melodramatic scene, he carves out the initials of the woman on his wrist. Shahrukh built this obsessive behaviour as a repetitive pattern in the films that followed – Darr and Anjam. He used the same anti-hero streak for a revenge drama in Baazigar.

Raju in Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, however, was a different person. A remake of Raj Kapoor’s Shree 420, he was a leftover from the ‘socialist 1950s’, getting a new life in the inherited progressive legacy of Aziz Mirza’s film. Here, too, the antagonism towards wealth and big business was apparent, though there was also the desire to make it big. The city corrupts the small town simpleton, but he is redeemed by the friendships and love that the same city gives. Over the years, Mirza was to revive this character again with Shahrukh, first, in Yes Boss, and then, in Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani.

And what if Raju had not left the small town for the city? This question was imagined by Shahrukh’s third film: Kundan Shah’s Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na,which, curiously, the actor calls his “most memorable role”.

Shahrukh won his first Filmfare award for Deewana in 1992. Brought up in Delhi, with no connection to Bollywood, this was no small feat. In the next few years, he won four diverse categories of Filmfare awards – Critics’ Best Actor, Best Villain and Best Actor, with a nomination for Best Actor in a comic role. “The only thing left now is to be nominated for Best Actress,” he remarked at an award function.

Filmfare awards have a culture-specific place in box office Bollywood – something only an insider can understand. It is no secret that the awards have nothing to do with talent, or authentic competition. Once upon a time, they must have been about acknowledging the most popular, which is bad enough, but today they are even worse – keeping everyone happy, ensuring that they turn up for the awards night show. And yet, most aspiring actors desperately want to be a part of this world, despite the predictable dance numbers, and brazenly unfair nominations and winners.

In the years to come, Shahrukh was to become a habitual winner of theFilmfare award, and a favourite at most award functions that propped up. Predictably, this secure position came with a tameness in the characters he played. The mad lover streak had been reigned in, the unconventionalness made conventional and ‘cool’. This was most visible in two big banner films – Aditya Chopra’s DDLJ and Karan Johar’s KKHH.

These films made Shahrukh ‘attractive and lovable’. Playing rich again, the focus now was on playing by the rules. In DDLJ, the conservative parents of the woman he loved had to be convinced that they should accept him, their conservative values intact. Conversely, conservativeness could not be so rigid, could it? In KKHH, the conflict was the confusion between love and friendship. Its great dilemma was whether one falls in love once or twice! Everyone ultimately was won over; the world was a nice place after all.

There was something inherently exhausting about these stories and characters. How long could he go on playing the same person? Perhaps burdened by the expectations generated by their first films, Chopra and Johar took to making too much of everything in their next films, Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (KKKG) and Mohabbatain – too many people in love, too many stars and stories. Clearly, the formula had a shelf life.

In the mythology of Shahrukh Khan built on his big banner lover roles, it is easy to overlook how the Raju persona also grew and changed. This was evident in films like Badshah, Yes Boss, Duplicate and One Two Ka Four, to name a few. Except in a film like Yes Boss, he played these ‘ordinary man’ roles by reducing himself to a comic hero, devoid of context or commentary.

It is interesting, then, that he attempted a return to that context when he turned producer, choosing to set up his Dreamz Unlimited Production company with Aziz Mirza and Juhi Chawla. Together they decided to make not a Chopra-Johar style movie, but a return to the themes explored in theRaju Ban Gaya Gentleman days. Directed by Mirza, this was Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani where Shahrukh is a ‘sold out’ TV journalist, constantly reminded of earlier days of idealism by his father. Eventually, he comes back on the right track.

The movie did not make money. And for Shahrukh, who sought nothing but singleminded populism (and huge commercial success) an average run at the box office meant a path not worth pursuing anymore. Perhaps his biggest problem, apart from his limited talent that restricted the roles he could do, was this obsessive desire for popularity. This inevitably meant that he would avoid making films that might challenge established cinematic idioms, but not guaranteed to be popular.

With the lacklustre response toboth Mohabbatain and Hindustani, Shahrukh went through a vulnerable phase. Ironically, it was a return to the ‘ordinary’ which rescued him and made it possible to retain his superstar image. Swadesand ChakDe! India expanded the idea of what Shahrukh could become, surprising those who thought they knew all his moves. Mixing the ordinary with patriotism, while Swades did not do so well, Chak De! was a hit. It was Yash Raj’s response to the ‘new wave’ that was beginning to emerge in Bollywood with new directors and writers having entered the industry. Roping in Jaideep Sahani, who had written the interesting Khosla ka Ghosla,Chak De!worked where Hindustani had failed.

Shahrukh’s speech at the Filmfare function where he got the Best Actor forChak De! is memorable because it is the last of its kind – in the next few years he was to stop making sense entirely. Perhaps Shahrukh knew exactly what his limits as an actor were: “I pray to Allah to give me the strength, courage and talent to be able to do films like Chak De!. As long as I live, I will not let you down,” he said.

This promise did last for a while. Along with him, Karan Johar and Aditya Chopra, big money kings of mushy designer films, tried to cash in on the contemporary trend of realistic films. Thus, Chopra returned with Shahrukh to make Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi where he yet again played the almost faceless ‘ordinary’ Surinder Sahani. And Johar tackled Islamophobia in a frivolous manner in My Name is Khan. Though both films became popular, they didn’t seem to do anything for Shahrukh, the clichéd actor, or the repetitive star.

Something was not right about these films, and the varied, smaller, intelligent films that were now being made in Bollywood made this even more apparent. Why would anyone watch Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi when they could see a more honest Bheja Fry instead? It was evident that Shahrukh was trying too hard to prove a point that no one was asking him to make in the first place, because everyone already knew the answer.

And even this was shortlived, indicating its hollowness. Since some years now, another process had acquired momentum. Shahrukh was transformed into a brand. We were bombarded by his images, relentlessly and mindlessly selling, breathlessly making money. He became a compulsive seller of miscellaneous products. He was everywhere: IPL, ads, hoardings, TV/music/reality shows/promos, dancing in billionaire wedding parties, T-20 matches, award shows, even inside private management institutes, saying things which no one understood, probably not even himself. Like in a recent Filmfare interview, he said: “I am a feeling no one can resist.”

It was inevitable, then, that this megalomania would get recreated on screen in the easily forgotten Ra.One and Don2. Predictability is now the undoing.

(This article was first published in Hardnews)