Sharmistha Ray

The reverberations of a giant passing are almost always felt. This time, it’s in the guise of Maqbool Fida Husain, arguably India’s greatest Modern painter. Husain, who was the artist incarnate, India’s resident Picasso and a household name throughout India and other parts of the world, passed away on 9 June, at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London, at the age of 95 as a Qatari citizen.

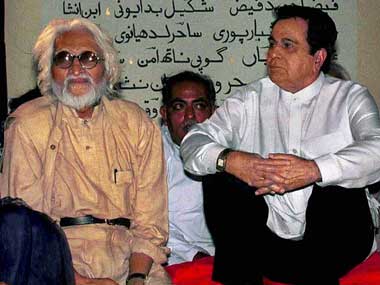

Always identifiable in his simple, unembellished attire, with his signature shaggy white hair and beard, Husain could be spotted in London or Dubai or elsewhere – a globetrotting barefoot maestro with a large paintbrush, neatly tucked under his arm. The physical description doesn’t do justice to the artist, who was up until his passing, larger than life.

After today, that spirit will loom much larger as the art world moves to consolidate his legacy, and understand his real contribution to art, culture and society. The results, I believe, will be astounding, if extremely complex.

Husain was an incredibly prolific artist with vast humanist concerns. Given the artist’s prodigious output, thousands of his paintings, sketches and art works are scattered around the globe, many undocumented. In recent times, Husain’s paintings have fetched millions of dollars at auctions and some have even been recalled as fakes. Deconstructing his legacy will prove a real task for future progeny.

Husain, and his Progressive counterparts, namely Tyeb Mehta, VS Gaitonde, SH Raza and FN Souza, led the art boom fuelled about a decade ago when audiences saw Modern Indian art works hit the Rs 1.5 crore mark. That seemed inconceivable for a generation of artists that produced art for art’s sake and not for commerce. Despite that fact, Husain reaped enormous wealth for any Indian artist of our times.

Born in 1915, in Pandharpur in Maharashtra, Husain’s rags to riches story is now the stuff of myth. Born into a humble Muslim family, Husain had a perfunctory education before moving to Bombay in 1937. An apprentice to a painter of cinema hoardings, he adapted the physical scale and flatness of paint application to his own painterly style.

In 1947, the Bombay Art Society annual prize led to an invitation from the Progressive Artists’ Group, a radical group of post-Independence artists comprising other Modernist legends FN Souza, Raza and Gaitonde.

The rest, as the cliché goes, is history. Padma Shree, Padma Bhushan, Padma Vibhushan, controversy, nude Hindu goddesses and Bharat Mata, and eventual self-imposed exile. The depiction of Mother India as a nude woman was an honest artistic expression, but ignited hard-line sentiments and forced him to spend the last few years of his life outside the country. That controversy also denied him India’s highest civilian honor, the Bharat Ratna, despite pleas and petitions from arts and cultural leaders in the country.

The controversy that alighted upon him was tragic, but Husain reaped its benefits too. He had homes in London and Dubai and lived the life. I recall an artist friend posting pictures on Facebook of a debonair Husain, wielding his paintbrush and leaning proudly against his beloved red Ferrari, which he was oft seen driving around Dubai.

In other pictures, he was breaking bread, and no doubt sharing stories, with other Indian artists, who looked on reverently as the Great Master spoke. According to those who knew him, he was exceedingly generous, profoundly well-read and a very astute promoter of his own brand. He was known to charge exorbitantly for his paintings, but when the spirit moved him, he gave them away for free.

Husain may have been Modern Indian art’s omnipresent evangelist, appearing to stoke public controversy and nationalist sentiment with equal vigour, but his true legacy lies in his art. Labelled as an iconoclast of sorts, ironically, his best paintings are nationalist emblems of an India forming its own identity in the wake of Independence.

There are the galloping horses, Mother Teresas and Ganeshes and obvious symbols of India for which he is famous, but Husain also created an entire visual lexicon for a new India.

His visual style derived from European Modernism, namely Picasso, but his dexterous application of paint in fluent strokes was all his own. He never belabored an image or an idea: he just painted. His subject was India. He painted everything from Hindu and Muslim religious festivals, Bollywood, mythology and history, to the life that unfolded around him in streets, homes, villages, men, women, children, babies, rich, poor, aristocratic…none of it was beyond his palette. All of it was fodder for his mammoth encyclopedia of our India.

There are no judgments in Husain’s work. By simply painting what he saw and felt, he overrode many social taboos, always with the deft curiosity of an artist and with the brilliance of artistic genius. With a few broad strokes of his brush he left behind an entire universe of images and stories that will become part of our shared history.

Artists have had a complex relationship to Husain saab. On the one hand, they revered and admired him, but on the other they also feared him a little bit. Every artist looks for acknowledgement and recognition. Husain had both in overabundance, but he liked being a pariah too.

I only ever caught sight of Husain once, and it was brief, in the most unlikely of places. During a Christie’s sale of Indian art in London last June, Husain sat just a few rows behind me, quietly watching as his paintings were auctioned one by one. His aura filled the room with a hush. I glanced back a few times, wanting to catch the Master after the auction, but he slipped out as quietly as he had slipped in.

Later, I heard he was at a gallery opening, socializing with the art fraternity. Such was his energy. He had to be everywhere, in the thick of things.

Once the smoke has cleared and the media mania has died away, Husain’s paintings will remain as enduring documents of a country he cherished. Despite his exile, and wanting at times to return to India, his final wish was probably to paint, paint, paint and that’s what he did up until the very end. Husain’s posthumous legacy will exceed the din of controversy, and in the museums of the future, the beauty and nostalgia of the past will come rushing back to us through his paintings, allowing us all to finally see what we could not while he lived.

Sharmistha Ray is an artist and writer living in Mumbai and New York.

The article first appeared at FirstPost Ideas (www.firstpost.com)