Abdul Khaliq for BeyondHeadlines

The Right to Education Act is discussed a lot but very few understand its provisions. There is overwhelming level of ignorance among politicians regarding the Act and its implications. Before I get into the nitty gritty of the subject, I wish to flag a few very relevant facts that should set the tone for the discussion on the RTE Act.

– India has the largest illiterate population of any nation on earth.

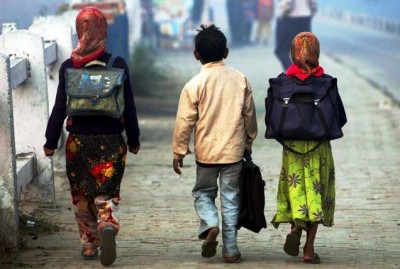

– It is estimated that at least 35 million, and possibly as many as 60 million children aged 6-14 years are not in school.

– The country’s literacy rate has risen from 12% in 1947 to 75% in 2011- much below the world average literacy rate of 84%.

– The 2011 census indicated a 2001-2011 decadal growth of 9.2% which was slower than the growth in the previous decade.

– In 600,000 villages, the education of the young is in the hands of barely qualified ‘para teachers’

-According to experts, incompetent teaching staff is one of the main factors affecting literacy in India.

– It is estimated that there are over a lakh unrecognised schools in the country, maybe many more. In the national capital, the number of unrecognised schools is estimated to be anything between 2500 to 10,000.

The data that I have given above was essentially to highlight the problems and issues that the RTE Act needed to address for fulfilling our founding fathers’ vision of universal literacy. The RTE Act had two main objectives viz; a) guaranteeing right to free and compulsory education to all children and b) imparting quality education. Has the Act provided the platform and impetus to fulfill these objectives? Having closely scrutinized the Act as also the Supreme Court judgment on the issue, I have grave reservations regarding the key provisions in the Act. The government has proposed a perfect but impossible solution to a burning problem-a formulation that is completely divorced from reality. In passing such an Act it seems that the government has been afflicted by the Marie Antoinette syndrome. Let me explain. During the critical food crisis in 1789 in France, when the then Queen Marie Antoinette was informed of the acute bread shortage in Paris, her laconic response was “Let them eat cake.” Similarly, the various provisions in the RTE Act betray the government’s insensitivity and colossal ignorance of the facts on the ground.

The Act has enunciated a grand scheme whereby within 3 years only recognized institutions with certain minimum infrastructure will impart education in the country. A laudable objective, no doubt, but impossible to achieve. On the contrary, Sections 18 and 19 of the RTE Act if implemented would cause incalculable harm to primary education in the country. The Act envisages that only schools that have the minimum teaching personnel and physical infrastructure that includes at least one classroom per teacher, a kitchen and playground, would henceforth be authorised to impart school education. At the present time when land prices have shot through the roof in cities, to conjure up a playground where there is none today is asking for the moon. Quite clearly, the denizens in the Education Ministry are unaware or uncaring that the stringent stipulations in the Act will result in a large number of the unrecognised schools as also aided schools being closed down. In my view, the negative obsession to close down unrecognised schools before alternative avenues of primary education are available is an unpardonable crime.

It is apparent that in the government’s view, the unrecognised schools are an unmitigated evil. It is estimated that out of the 6 lakh odd schools in the country, almost one-third are unrecognized. What the government has conveniently forgotten is that since Independence, the unrecognized Schools have been filling in for the non-existent government schools. One commentator has attributed the rush for admission to unrecognised schools to the fact that standards in government schools are dismal, forcing parents to look for alternatives. The reality is that we have good and bad unrecognised schools in our midst. The only fairly comprehensive study of unrecognised schools was done in Kerala some years ago. According to this study in 2004 there were 2646 unrecognised schools in Kerala with about 3.5 lakh students. The study arrived at the following assessment of unrecognized schools in Kerala;

“Most of the teachers are well-qualified and they impart good coaching to their students…Most of the schools…impart good education in every sense. The school system provides employment to a large number of qualified unemployed persons as teaching and non-teaching staff. The numbers of such unrecognised schools are increasing day by day. As a result, numbers of students enrolled in aided schools are decreasing and it may affect the stability of the aided school system… Most of the teachers are well-qualified and impart good coaching…even though they are well qualified, they get very low salary.” It is quite apparent that in Kerala, at least, the unrecognised schools are invaluable in imparting good education to the children, though; admittedly, the experience of other States could be quite different. However, what the RTE Act has done is to put all these organisations, the good and the bad, under threat.

As one who has experience of dealing with education department officials (my family runs a few schools in my hometown in UP), I am deeply perturbed to see that the RTE Act, by giving absolute power to the Education Department and local bodies to make or mar unrecognised schools, will become the ideal tool for large-scale corruption. Even when there was no specific law against unrecognised institutions, the school inspectors had to be ‘appeased’ even if the school had done nothing illegal. Now with the RTE Act in force, the inspectors will have a free rein to force school authorities to do their bidding—a grim portent for the future. I foresee a large number of undeserving schools getting recognition and a good number of meritorious schools closing down.

We must not forget that at present, between 35 million to 60 million children are not in school. If the number of schools come down in number, as they certainly will, due to closure of unrecognised schools that do not comply with the stringent infrastructure standards, the nation’s goal of ensuring universal literacy would suffer a massive set back. The RTE Act bases its formulations on the absurd premise that the recognized schools would not only be able to accommodate the students from schools that close down but also have room for the new entrants to school. Can it get more absurd than this? The consensus among experts is that government schools are generally not only overcrowded but impart a very poor standard of education. Moreover, a recent study of 188 government run primary schools revealed that 59% of the schools had no drinking water facility and 89% no toilet facilities. And yet ironically the government schools would be the most secure under the new dispensation envisaged in the RTE Act.

The most outrageous aspect of the RTE Act is that it treats select government schools as more equal than others, and seeks to insulate them from the upheavals triggered by implementation of the Act. By all accounts, the only government schools of a reasonable standard are the Kendriya Vidyalayas and the Navodaya Vidyalayas, which the Act has earmarked as the “specified category.” Significantly, vide section 5 , these schools are exempt from accommodating children who seek transfer from schools which have no provision for completion of elementary education. An Act that professes to strike a blow for egalitarianism and equal educational opportunities for all children has no business to accord preferential treatment to these schools.

According to the experts, inefficient teaching staff is one of the prime factors affecting literacy in India. It may surprise you to know that the vital, life- moulding primary education in most of our 6 lakh odd villages is in the hands of barely educated ‘para teachers’. The qualification for becoming a ‘para teacher’ or ‘contract’ teacher in most of the States is higher Secondary or even a Secondary pass, but in Rajasthan the qualification for the para teacher is 8th Standard for males and 5th standard for females. What kind of education can such individuals impart? Paradoxically, the RTE Act concentrates all attention on number of teachers per class and physical infrastructure buy pays scant regard to the most vital aspect of education, namely, quality of teaching. Significantly, the RTE Act in Section 7 (6 ) ( b ) blandly and generally states that the Central Government “shall develop and enforce standards for training of teachers.” The Act however, has, in Section 23, ratified “relaxation in the minimum qualification required for appointment as a teacher” for up to 5 years, whereas no such concession is granted in relation to physical infrastructure. Clearly, the RTE Act accords little importance to teaching standards, which is the major shortcoming in our educational system.

The RTE Act is littered with utopian, unworkable statements of good intent. For instance, Section 4 directs that where a child is admitted to a class appropriate to his age, he shall, in order to be at par with others, have a right to receive special training. Section 8 commands the Government “ to ensure compulsory admission, attendance, and completion of elementary education by every child of the age of six to fourteen years.” Section 11 takes the cake and therefore deserves to be fully quoted: “With a view to prepare children above the age of three years for elementary education and to provide early childhood care and education for all children until they complete the age of six years, the appropriate government may make necessary arrangement for providing free pre-school education for such children.” We do not have the wherewithal to provide primary education to all, and yet the Act envisages universal pre-school training facilities also being set up.

In the ultimate analysis, perhaps the only praiseworthy clause in the RTE Act is Section 12 which mandates that every recognised school, even if it is unaided, is obliged to admit in Class 1, to the extent of at least 25% of the strength of the class, children belonging to weaker sections and disadvantaged groups and provide them free and compulsory elementary education.

For too long has good education been a service that only the well to do can buy. I do not accept the absurd elitist argument that the children from the weaker sections would be misfits or that they would pull down the overall standards. In an unequal society, where quality education is available only in select schools that have been beyond the reach of the poor and which give their students a head start in all future professional pursuits, it is only appropriate that children from less privileged backgrounds are given exposure to such an education. That’s what an egalitarian society is all about. This is a small but important step towards breaking the citadels of privilege that many institutions have become in this country. It is therefore heartening that the Supreme Court has upheld the constitutional validity of this proposition in the RTE Act. However, it is disappointing that the Court has also endorsed the impractical and potentially destructive provisions in the Act. There is also the big unanswered question of the fate of the children from the weaker sections after their free elementary education in the elite schools, where the monthly tuition fee would be equal to the annual income of their parents. What is their fate after they attain the age of 14 years? Your guess is as good asthat of the Education Ministry which has left this issue open-ended.

How will the implementation of the RTE Act impact the Muslim community which is educationally the most backward of all in the country? According to a survey conducted by the Social and Rural Research Institute, the share of Muslims in the out of school children is 13.05 % against the national average of 9.9%. Unfortunately, the RTE Act will only further widen the gap. At present, Muslims in the cities are mainly segregated in ghettos where, for reasons well-known, there is lack of basic services, especially schools provided by the government/ local authority. As such, Muslim children are largely educated in unrecognised schools that have mushroomed within the ghettos. For instance, there are over 30 unrecognised schools in Jamianagar alone and most of these schools do not possess the “minority school” certificate. While some of these schools may get the certificate, the others will have to shut down for failing to meet the exacting standards laid down. With the few government schools in the neighbourhood already overcrowded, I foresee a large number of Muslim children abandoning schools altogether or reverting to obscurantist madarsa education for want of an option.

(The author, a former civil servant, is Secretary General of Lok Janshakti Party and can be contacted on akhaliq2007@gmail.com)