Muslims carry the double burden of being labelled as anti-nationals and being appeased at the same time. —Rakesh Basant

Afshan Khan, BeyondHeadlines

Have you realised that due to the brutal killing of Muslims or to put it in other words, due to the increased incidents of lynchings, Muslims are feeling so insecure that their whole attention has gone towards saving their lives? Where did the question of unemployment and other social backwardness go? One can utilize the book, Denial and Deprivation as a resource to counter the myths and negative stereotypes spread by the BJP about Muslims. Hindutva forces try to

The book, Denial and Deprivation: Indian Muslims after the Sachar Committee and Rangnath Mishra Commission Reports by author Abdur Rahman, an IPS officer posted in Maharashtra, tries to evaluate the proceedings after almost a decade of the Sachar Committee Recommendation (SCR) and Rangnath Mishra Commission report (RMCR). It assesses the shaggy implementation of these two reports and provides suggestions for different issues to be solved at different government levels. It has critically examined the role of UPA 2 and the NDA government. While the UPA 2 did not give priority to the implementation of the reports, the NDA government openly adopted an anti-Muslim stand. It does not only gauge the roles played by different g

He has also covered the demands of different groups which fought for seeking the attention of the government towards the recommendations, from protesting on roads

Most of the recommendations of Sachar have not been implemented but the author admits that on the grounds of educational reforms, scholarships have been given to the Muslims but this is also limited. This limited scholarship, Rahman argues will not bring a change in the roots of the problem.

Interestingly, the book has chapters on Urdu, Madrasa and Wakf properties. These are those topics which do not usually appear in the mainstream discourses.

He argues that a section of media in India has created a perception that madrasa education is preferred by Muslims over school education and that it encourages religious fundamentalism and a sense of alienation from the mainstream. Rahman argues that these perceptions have been created in the absence of statistical data and supporting evidence. Though this proportion is as low as 9 to 10 per cent, Muslims want to send their children to schools for secular education but lack the opportunities. He lists many more reasons for this. He has tried to deal with the conspiracy to defame madrasa.

The book reveals many unauthorised occupations by governments and agencies. Some of the facts about wakf which made headlines in the media a couple of years ago has been given space in the book. He has given examples of many public places which are built on Wakf lands like the Millennium Indraprastha Park is built on Qabristan Ahle Islam land. The archaeological survey of India has also encroached upon dozens of graveyards in the capital alone. He criticises the authorities for adopting anti-Muslim stands by stating that these Wakf lands are made a hub of anti-social elements and all the wrong activities are allowed except Namaz.

The book will help those who are still confused between the two reports. He has clearly drawn the differences between the two reports and the strength and weaknesses of both the reports. It reminds us of the responses of different groups of society towards these reports, particularly the Hindutva forces. Pravin Togadiya went to the extent of calling the RMCR as anti-national and anti-Hindu. Shiv Sena also threatened agitation if the government thought of implementing this report and even asked the then PM to throw it to the dustbin.

The author critically examines the roles of the regional Muslim base parties which demanded the implementation but his question is- ‘what did THEY do’?

Discourse on ‘Minority’ in the book begins with giving a dictionary meaning of the word to the condition of Minorities and reports released to understand the status of Minorities all over the world, connecting it with the discussion of Constitution of India containing the articles to secure the rights of religious minorities.

“One should understand that rehabilitation of riot victims, initiatives to uplift poor and affirmative action to compensate injustice are basic civic and human rights of Muslims. T

The book shatters away all the myths about any special favour or appeasement which the Hindutva forces kept on insisting, in fact, the figures indicate marginalisation and suffering of Muslims.

Appreciating Muslims, the author says that one positive thing in the last decade is that the attention of Muslims has shifted from religious and sentimental issues to educational and social upliftment.

Rahman ends the myth of “Hindu Khatre Mein Hai” and that there is a rapid rise in Muslim population. He has presented data in this regard and also argues that family planning is not something against the spirit of Islam. Though he has supported his arguments with some examples but does not engage with the religious texts directly in the same way as many other Muslim scholars in India have been doing. Most of these scholars do not give their own interpretation of their religion but tend to look into others’ argument.

Among many suggestions, one of the biggest suggestions of the author is that it needs to be recognised that there are SCs and STs within the Muslim community. He suggests that the government should go for a

Identifying some lapses on part of the community, the author criticises Muslims for spending crores on Mushairas, Ijtimas and Iftar parties. He suggests that this heavy amount can be utilised in many community development works. Discussion of ‘Abundant talent’ and ‘individual initiatives’ will prove to be a step forward in motivating the youths of this community. It will instil the feeling of community development and self-reliance in the ‘real’ leaders to do more works of welfare at their own, instead of relying wholly on Govts.

As per the Civil Lists of Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Foreign Service (IFS) and Indian Police Service (IPS) available in 2006, Muslims were found to be only 3 in IAS, 1.8 in IFS and 4 per cent in IPS. Moreover, most of the Muslim officers have been inducted to these services as ‘promoted candidates’. (p: 307)

Apart from the above mentioned data about Muslim representation in Administration, he has also provided facts regarding the representation of Muslims in judiciary and Indian Army.

He criticises the government for wasting energy and time on the surveillance of Madrasas, instead, Rahman suggests that it should focus more on mainstream education to the children of

The author shows evidence that Muslims are living with pathetic job conditions and standard of living. Lack of drinking water facilities, latrine facilities and garbage disposal facilities to Muslims which are all related to the health and hygiene, are contributing to and witness further marginalisation.

His knowledge seems to be up to date as most of the references he has cited are from online sources. Despite being in the service, criticising the authorities is an act of courageousness and valour.

Name any Muslim related issue in the

The book Denial and Deprivation, however, paves the way for those who want to work on Muslim issues in India. There is no doubt that it will be used widely for reference by the students, academicians and journalists. The book is written in a very simple language which can be understood by general readers.

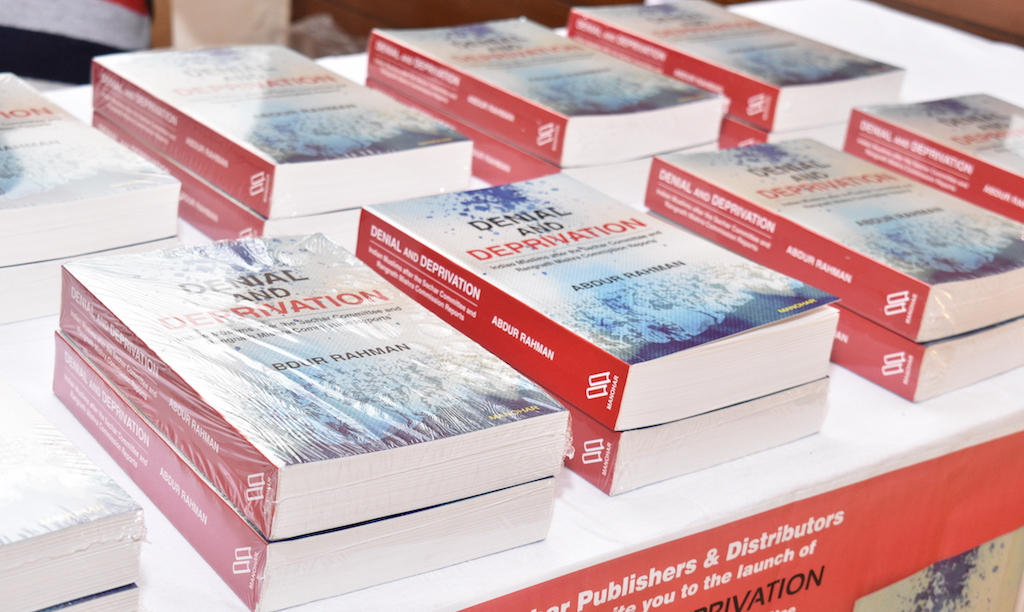

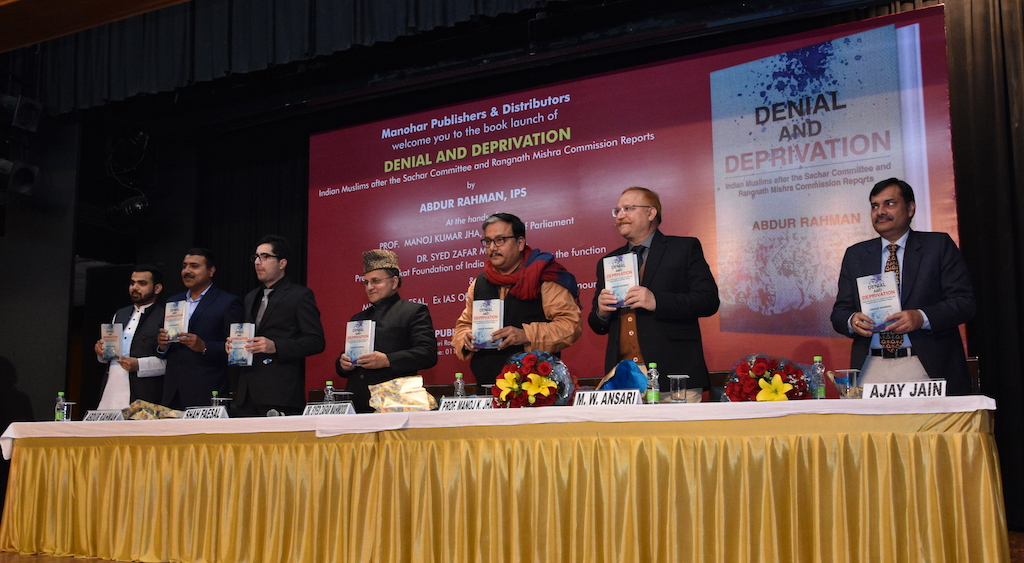

Book— Denial and Deprivation: Indian Muslims after the Sachar Committee and Rangnath Mishra Commission Reports

Author— Abdur Rahman

Publisher— Manohar (2019)

ISBN— 978-93-88540-03-2

Pages— 569

Hardcover Price— 1595

Paperback Price— 695