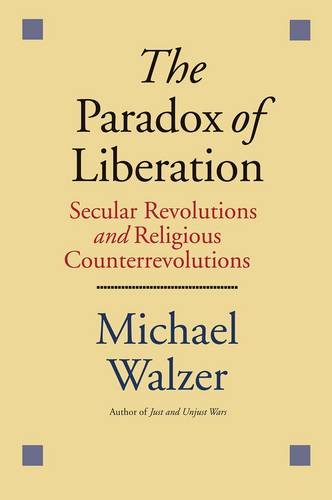

‘The Paradox of Liberation’, by Michael Walzer, an American political thinker, deals with the paradox of national-secularist movements which create the religious revivalism after the liberation of a country under foreign rule.

For the analysis of ‘disturbing’ patterns in the history of national liberation, Walzer examines the creation of three independent states in the years after world war II; India and Israel in 1947-48 and Algeria in 1962.

He inquires into the cases of the aforementioned democratic countries that why after 20 or 30 years of independence, they had to face religious counter-revolutions. Furthermore, why the states that exist today are not the states envisioned by the original leaders and intellectuals of the national liberation movements.

The book deals with the conditions prevailing in India, Israel, and Algeria during the national liberation movement. He also analyses the post-independence scenario in these countries to assess the achievement or failure in terms of secularism.

It evaluates the role of the common people in these countries, the liberation leaders, the colonizers; and more importantly, the religious militants. He argues that national liberation is an ambiguous project. The nation has to be liberated not only from external oppressors but from the internal effects of external oppression.

More importantly, the book discusses the stages that liberators go through. They first realize that they need to raise the consciousness of the people and then they have to fight with the traditionalists.

Religious Revivalism

The book explains the failure of the liberators and militants to consider tradition as something which has a long-lasting impact on societies.

Moreover, the problem of religious revivalism puts a question on the success of the liberationist movement.

Explaining the scenario in Algeria, he says that the French repression was more brutal than that of English. But sadly, it was mirrored in the brutality of the FLN’s (National Liberation Front) internal war and FLN’s post-independence authoritarianism.

Commitment to secular liberation in Algeria was weaker than in other cases. Apart from the militant dominance, he also discusses the Muslim moderators in Algeria who were opposed to FLN’s militants.

Going into the case of Israel, he brings in attention the rivalism between Zionism and Judaism.

For explaining the paradox in this region, he mentions leaders such as Herzl who was a nationalist leader, who looked at his own people with a foreign eye. He dreamt of Zionist Utopia.

Zionism was marked simultaneously by a deep commitment to the Jewish people, and by an equally deep commitment to the transformation of Jews.

He argues that the biggest problem in Israel was the lack of collective action. Israel faces the problem of fierce nationalism. The Orthodox Jews, the Haredim do not really think of the state as their own. They do not recognize a ‘good’ that is common to themselves and all other Israelis. It leads to the political culture of passivity.

Odd case of M.K.Gandhi

Walzer further argues that though there are many commonalities among the three cases, there are minor important differences too. For supporting his argument, he compares the attitudes and vision of M.K.Gandhi and Nehru with leaders of the two other countries.

For each of the three cases, one thing that Walzer concludes and suggests is that the liberators should have engaged with the tradition, culture, religion of people. The way these factors shape the society. Referring to scholars like Ashish Nandy and Akeel Bilgrami, he argues that Nehru was too optimistic about the secularization as an inevitable achievement in the long run.

Far from engaging with the native people and their culture, the ‘liberationists’, they were more familiar with the other nations, specifically the imperialist countries. Neither were they interested in bridging the gap with the people they wanted to liberate and they did liberate.

Therefore, ‘Nehru spent eight years in British schools and, as a young man, was probably more conversant with the history and politics of Britain than with the history and politics of India.’

Late in his life, he reportedly told the American ambassador John Kenneth Galbraith, “I am the last Englishman to rule India”.

Similarly, Walzer cites the example of many leaders from India and the two other countries who had closer ties to foreign countries more than their own.

‘…the militants of national liberation are the carriers of ideas that are largely unknown to the people, or most of the people, to whom they are carrying them’ (p. 18)

But the militants raise the hope of newness and give it body in one of the modernist ideologies—nationalist, liberal, socialist, or some combination of these three. Here, Walzer argues that for them, the old ways must be overcome and they demand the people to break the ties with the established authority. But at the same time, old ways are cherished by many of the men and women whose ways they are. And this is what Walzer calls, ‘the paradox of liberation’.

Walzer does not mean that these leaders are not successful but he argues that liberators do win in their fight against the oppressor foreigner rulers and people do join them even if they do not share the ideology being offered to them.

He contends that the odd case in this schematic story is Mohandas Gandhi who succeeded in turning traditionalist passivity into a modern political weapon. There is no comparable figure in Zionist history or in the FLN. Gandhi even though openly opposed Hindu beliefs and practices, he spoke to the people in religious language.

‘In Israel and Algeria, the transition from national liberation to religious revival was accomplished without the mediating role of a Gandhi figure, so perhaps Hindutva, the ideology of Hindu-ness, would be a powerful presence in Indian politics even if he had never inspired and led the liberation movement.’ (p. 21)

Therefore, all those who blame Gandhi for Hindutva as a dominant ideology in the post-independence era, forget that he was the only leader who used religious language and negotiated with the tradition.

In a nutshell, the book raises and attempts to answer questions such as what did the liberators achieve? What after gaining independence? Why is there a traditional revivalism? Why governments compromise on the principle of secularism? How to engage the different sections of society in the process of political development?

Book: The Paradox of Liberation; Secular Revolutions and Religious Counterrevolutions

Author: Michael Walzer

Price: ₹ 1,070

Edition: 2015

Pages: 192

Publisher: Yale University Press