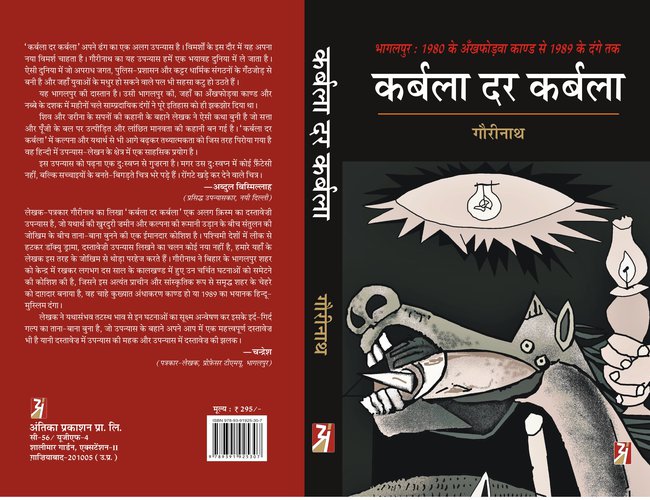

At least recently published Indian language novels document the rise of oppressive hegemonic majoritarianism also in India alongside the resistance to it. Vaidhanik Gulp by Chandan Pandey (rendered into English as Legal Fiction by Bharat Bhooshan Tiwari); Qabar (The Grave, a Malayalam novel by K R Meera rendered into English by Nisha Susan and the latest one is Karbala Dar Karbala (Hindi novel) by Gourinath, which has sold out over 1100 copies in just four weeks of being launched.

Karbala Dar Karbala is located in Bihar’s silk town, Bhagalpur, during the 1980s, where the events culminated in an unprecedented communal massacre and massive displacement of a huge Muslim population across the town and in 250 villages of the district. Gourinath, the novelist, was an undergraduate student of sciences in Bhagalpur during the said decade. Through a mesmerizing style of story-telling, taking creative liberty, he meticulously unpacks the entire process of criminalization, communalization, and its political economy. He makes it an insiders’ account even while benefitting from reports investigative journalism, inquiry reports of the government committees and of civil rights groups, besides social science commentaries and essays.

In Hindi-Urdu creative prose, we don’t find a strong tradition of writing accounts of cities and villages Shahrnama and GaoN-nama. The scholar-journalist Arvind N. Das (1949-2000) converted a historical account (1987) of agrarian and socio-economic change during the four (16th to 20th) centuries, in his native village, Changel (Muzaffarpur, Bihar) into a novel (1996).

At the beginning of the 1980s, the silk town had earned huge disrepute when a horrific series of incidents had taken place: police was blinding the criminals. Unusual for novels, Gourinath goes on to give references just as Qurratulain Hyder (1927-2007) did in her autobiographical novel, Kaar-e-JahaaN Daraaz Hai. This provides his gripping creative depiction with profound authenticity.

During the 1970s and 1980s, various smaller towns had gone into the grip of gangsters. In most of these cities, the gangsters and majoritarian communal outfits merged with each entrenching the communalization at the lowest level. This phenomenon in the smaller towns (and more recently in villages too) remains largely unexplored by both social scientists and novelists. For the mega-cities such as Bombay of the 1980s, Gregory D Roberts wrote a thick novel, Shantaram (2003) and for Kanpur, Kathinka Froystad wrote a well-researched historical account (2005), Blended Boundaries: Caste, Class and Shifting Faces of ‘Hinduness’.

Gourinath may be the first novelist to have paid meticulous attention to a small town, which is prone to communal strife since the 1920s. This is a brave account in exposing the villains and heroes, the dramatis personae, of these sordid realities, with guts. Only the names of some of the characters have been changed, otherwise, real names of the politicians, bureaucrats, police officers, and criminals have been retained.

The plot revolves around Shiv Jha, a bright student, who comes from a village near Forbesganj (Saharsa) and reaches Bhagalpur to pursue his college education. While writing his examinations for MA (History) in October 1989, the city gets engulfed into an unprecedented communal massacre that continues for the next few months, spreading into 250 villages of the district. Police being blatantly on the side of the rioters, the pogrom is followed by huge displacement of Muslims and their land grabbed by local Hindu influential and toughs.

Another central character of the story, Zarina, is a sharp and vivacious student, but, in the hours of crises, she reveals her traumatized psychology. The daughter of an upright judge got traumatized at seven years of her age, in 1973, when her father’s official residence was attacked by criminals as he had refused to buckle down under the pressure of the corrupt collector and police chief of Muzaffarpur (Bihar).

In the 1970s, as a schoolchild, Shiv could notice anti-Muslim cultural prejudices and hatred in his own family and village. At the same time, his best friend in the village school was a Muslim, Taslim. Shiv, thus, gets troubled with the inexplicable anti-Muslim hatred harbored by his fellow villagers. He also encounters deep patriarchy prevailing in his society. Shiv is even more disturbed by the fact that even the educated, affluent and influential people tolerate many kinds of injustices prevalent in his village. A man kills his own brother, grabs all his landed properties, subjects his brother’s widow to all kinds of exploitation reducing her to his own sex slave, goes on to expel his only nephew, Mudit, out of the house. He takes shelter in an old dilapidated house at the far end of the village. Mudit is killed after he takes a poor Muslim girl from the village in his marriage. He somehow manages to escape and disappear. Shiv’s own elder brother resorts to many kinds of vices including extra-marital affairs with poor Muslim girls. Yet, the influential people of the village don’t protest against all these.

Having gone to Bhagalpur in 1982 to pursue his education, Shiv Jha, from very close quarters, witnesses rising crime, police-gangster nexus, political patronage to these elements by the then chief minister and speaker of legislative Assembly, both Brahmins and legislators from the same town, who indulged in intra-party factional fights for the top position. By then, in 1981, Biharsharif (Nalanda) had already suffered communal violence.

Shiv observes changing caste composition of the criminals and their gangs, and then suddenly these gangs get polarised along communal lines, as the Ram Mandir Movement was peaking soon after the Shah Bano legislation against the Supreme Court verdict of April 1985, not to say of the Hindutva reaction against the Meenakshipuram (Tamil Nadu) conversion of 1981.

By now, the criminals in Bhagalpur and elsewhere were fattening themselves through contracts for construction, kidnapping for ransom, land-grabbing, and investing these into making shopping complexes, cinema halls, transport entrepreneurship, etc. The lower caste criminals were increasingly being killed by the police in fake encounters, facilitating ways for the gangsters of the upper caste and upper intermediate castes. The Dalit police officer (IPS, 1973) who had started his career with blinding the Bhagalpur criminals in 1979-1980, ended up as a BJP parliamentarian from Palamu (Jharkhand) in 2014.

Two Muslim gangsters were also there in Bhagalpur who were used to escalate the communal flagration in late October 1989. The novel however avoids the details pertaining to rise and nemesis of the gangsters. Nor has it depicted the phenomena of the 1970s such as agrarian distress, the rise of Naxalism, and academic degeneration of the Bihar campuses after the Jai Prakash-led Total Revolution (1974). The rise of the saffron forces via struggle against the Emergency (1975-1977) and subsequently Rightward shift of the ruling Congress in the 1980s, stoking communalisation of society and polity, is an important aspect that is beyond the time-frame chosen for the story.

The novel however does take care of depicting that as late as the 1980s, such provincial mofussil universities had a considerably vibrant academic and political culture of studies, debates in and outside classrooms, on tea-stalls, river ghats, and elsewhere. In their conversations and discussions, they comment upon the majoritarian shift of the ruling Congress in the 1980s, their connivance with the RSS leader Balasab Deoras (1915-1996), the anti-Sikh massacre of 1984 with which Bhagalpur was affected very badly, traumatizing one of their fellow Sikh friends, Satvir. The family and friends with their camaraderie and counsel rescue Satvir from the depression.

The novel owes its title from (a) the outrageous and instigative public statement of the then district police chief, KS Dwivedi (who recently retired as the police chief of the province). He threatened the Muslims that they will be massacred as the one had happened at Karbala (Arab) in the 7th century AD; (b) a conversation of a professor with a group of students in a hospital where the professor was undergoing treatment having received injuries by the hoodlums of a majoritarian student outfit. In the face of a fast deteriorating communal and administrative atmosphere, the professor counsels his hopeless student activists by saying that the communal forces may resort to massacres after massacres (Karbala Dar Karbala), but history will expose the killers and will make common people spit on their faces.

Through the character of a professor of history, the novelist tells us about the processes and agencies of communalization in Bhagalpur which results in the violence of 1946 and 1967. Family of one of the students suffered in each of those incidents of communal violence. Finally, in the violence of 1989, the student, Sarfaraz, along with each member of his family is wiped out. They were modern in outlook, pluralist in social interaction and in everyday life, despite the fact that their trade, silk industry, and even their men and women suffered in each incident of communal violence in Bhagalpur as well as in the Ranchi-Hatia violence of August 1967, which had erupted against the demand of Urdu to be made second official language.

This small group of bright and progressive students had formed a study circle, marginally helped by their teachers, who brought out pamphlets, handbills, street-plays, evening schools in slums, and other such interventions. In the face of majoritarian outfits of students and youth affiliated to the RSS and patronized by the regime, these civil society interventions were increasingly becoming helpless and least effective. The Ram Temple movement had arrived and the social spaces (on the campus as well as in the city) were being deeply communalized through grand public celebrations of festivals and sports. According to a Hindi memoir (Meri YaadeiN, Meri BhooleiN) of the then chief minister, Satyendra Narain Sinha (1917-2005), an immediate flashpoint of the massacre of 1989 was a dispute in the cricket match played between the teams led respectively by the collector, Arun Jha, and the district police chief KS Dwivedi.

The Muslim share of conservatism, patriarchy, and communalization have got the least space in this fictional narrative. Even the reaction of Zarina against the Shah Bano episode is kept rather vague. The Muslim communal outfit, Aql-e-Hayat, is mentioned only in a passing way. There is a general accusation against the liberal-Left-secularists in India that they often go soft on Muslim communalism and retrogression. This novel too suffers from this limitation.

The sordid tale of the Shah Bano episode, therefore, needs to be recounted here.

At 60, Shah Bano (1916-1992) was pushed out of her house by her husband (an affluent advocate in Indore), by her sons and daughter-in-law. In 1975 she approaches the Indore court asking for maintenance from her husband. In April 1978, right inside the court, in the very presence of the judge, her advocate husband pronounces un-Quranic instant triple divorce. Thus he uses the Muslim Personal Law as an instrument just to circumvent the payment of maintenance. This case reaches the Supreme Court where, in 1985, she gets a verdict for a meagre amount of maintenance, Rs 179/- per mensem.

Meanwhile, Ali Miyan Nadwi (1914-1999) and his companions mounted enough pressure on the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi (1944-1991) to legislate a law against the court verdict. The Momin Conference Parliamentarian Ziaur Rehman Ansari (1925-1992) extracted a promise from Rajiv Gandhi in the Siri Fort Auditorium (Delhi) on January 15, 1986, to that effect. A deal was struck that in exchange for this, the lock of Babri Masjid will be opened. Accordingly, the Faizabad court delivered its verdict on February 1, 1986, to open the lock and within an hour of the verdict opening of the lock was broadcast on the government-owned TV news channel, Doordarshan. Ali Miyan’s Urdu memoir (1988), Karwaan-e-Zindagi (vol. 3, chapter 4, p. 134, 157), and Nicholas Nugent’s book (1990), Rajiv Gandhi: Son of a Dynasty (p. 187) clearly testify this. The novel should have brought out this expose.

Even small towns such as Bhagalpur and Muzaffarpur had cosmopolitanism and pluralities. This novel tells us about the way such linguistic identities were forced out to foist homogeneity upon these towns through crime and communalism. This novel is also a story of persecution and displacement of the Bengalis settled in some of the cities of Bihar. Bhagalpur and Muzaffarpur were such towns. The land-sharks, criminals, and politicians forced the Bengalis out of those towns. As recently as in September 2012, in Muzaffarpur, a girl, Navruna Chakravarty, was kidnapped and she is yet to be traced and recovered. For the common town populace, it is an open secret as to which land mafia, criminal-politician in connivance with which high ranking police officer perpetrated this crime. But nothing has happened to those criminals as yet. Soutik Biswas reported the spine-chilling story, “A kidnapped girl, a skeleton and a house of memories”(bbc.com, November 1, 2018).

There were several gang shoot outs inside the university campus of Muzaffarpur. In 1983, one such notorious gangster, Mini Naresh was done to death. A Chandigarh-based Hindi journalist of Muzaffarpur, Kunal Verma, an eye-witness to some of those incidents, wrote a six-part report (September 25-30, 2018) on the gangsters of Muzaffarpur. By then, the hostels of the campus had become known for storing arms by the communal outfits. In February 2018, the RSS chief had camped there. This was followed by a series of communal clashes in and around the district of Muzaffarpur (see my essay on www.twocircles.net, March 7, 2018).

Bhagalpur is closer to Monghyr which has been a center of manufacturing fire arms and ammunitions. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was a thing of common knowledge in Muzaffarpur that campus and city were infested with Bhumihar gangsters of Monghyr (particularly Begusarai). This is a majoritarian privilege of narrative-making and stereotyping that the said caste or the said campus is never stereotyped on this basis. This is unlike a Muslim-dominated campus of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) which is often subjected to stereotyping once an incident comes to light where a wrongdoer would happen to have any past connection with the AMU.

Gourinath has escaped these aspects. He has focussed on Bhagalpur, and the rural landscapes of the adjoining districts from where students, traders, as well as criminals flocked to the city of Bhagalpur. He devotes a chapter on the RSS shakhas and recruitments in the 1980s, as well as communally discriminatory relief works in the flood of 1987 and the earthquake of 1988. This reminds us of Edward Simpson’s 2014 book on Gujarat, Biography of an Earthquake. Simpson exposes the communally motivated and profit-extracting investment of the NRI Gujaratis in the relief works of 2001.

The disclaimer of the novelist is that it is his attempt at writing love in the midst of hate and carnage. Fact is: the novel is brave documentation of our national shame. The victims are often preached to forget the persistent massacres and move on. Our national conscience refuses to wake up when tribes, Dalits, and minorities are subjected to massacres. The perpetrators are usually kept nameless and faceless, and the judiciary often lets them off for what they call “want of evidence”. Gourinath’s novel is a protest against all such misdeeds. Our criminal justice system has perpetually been suffering from chronic ailments, exposed in Warisha Farasat’s 2017 book, Splintered Justice.

This powerful novel is brave experimentation in novel-writing where documented facts are fictionalized, with creative finesse and sensitivity. It is a strong reminder of such wilful failures of us as a nation. It makes a necessary reading in the harsh and challenging era of state-sponsored divisiveness that this country is currently passing through. This is what Samuel Eliot Morison (1887-1976), in his essay, “History As a Literary Art”, suggests: “Most writers of fiction are superior to all but the best historians in characterization and description”, to which one may add, ‘articulation of human emotions’.

Mohammad Sajjad teaches Modern and Contemporary History at Aligarh Muslim University and is the author of Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours (Routledge 2014/2018 reprint).

[Abridged version of this essay was carried by the NewsClick.In]