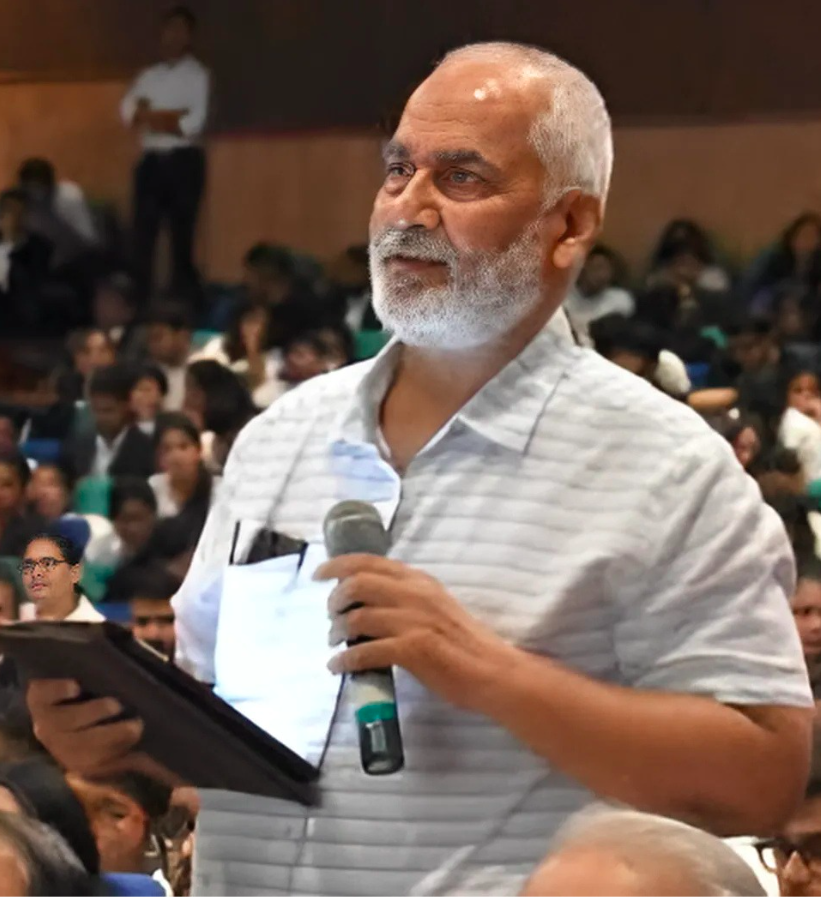

This is the third interview in our BeyondHeadlines Waqf Interview Series. In today’s issue, we spoke with Akramul Jabbar Khan, a retired Chief Commissioner of Income Tax based in Pune, India, who now serves as the Mutawalli (trustee) of the Alamgiri Masjid Waqf Trust in Pune with approximately ₹500 crore worth urban property which the committee plans to develop as a social service hub and revenue churner to finance scholarships, and providing financial assistance to the poor and needy — a model for utilisation of Waqf properties.

Born in Fatehpur district, Uttar Pradesh, Mr. Khan has spent the last 12 years raising awareness across India about Waqf-related issues. He holds a master’s degree in English Literature from Aligarh Muslim University. Deeply beholden to Baba-e-Qaum Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, his mission is to pay off some of his debt through social service to enrich the impoverished.

In 1974, Mr. Khan was selected for the Indian Police Service (IPS) through the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC), India’s top civil services examination. However, due to a color vision deficiency, he could not join. By the time he received the offer for DANI police, he had already been selected as a Deputy Collector through UPPCS and was serving in Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh, as a deputy collector.

In 1975, he took the UPSC examination once again and was selected for the Indian Revenue Service (IRS). His career as a taxman took him across multiple Indian states—Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh—before he, on retirement, eventually settled in Maharashtra, where he served as the Chief Commissioner of Income Tax in Pune.

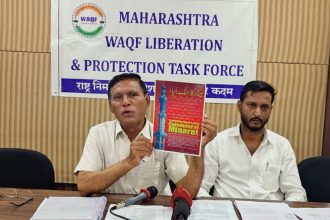

Currently, Mr. Khan serves as an advisor to the Maharashtra Waqf Liberation and Protection Task Force and a director in Waqf Liaison Forum, a charitable company. He dedicates his time to mentoring social workers, guiding efforts to protect Waqf properties, and mobilizing sections to advocate for their preservation and rightful use.

BeyondHeadlines had the privilege of an exclusive conversation with Akramul Jabbar Khan. Here are some key excerpts from this insightful discussion with a ground-level worker.

You have long been engaged with Waqf-related matters and have closely observed the challenges facing the Muslim community in India. How do you assess the approach of Muslims, particularly Muslim organizations, toward the Waqf issues?

Barring Kerala—and perhaps a couple of other states—the overall scenario is utterly disappointing and disheartening. In reality, there appears to be no serious strategy or committed approach for the utilization and development of Waqf properties to benefit their intended beneficiaries. Even the most unsettling and significant event of 8th August 2024 has failed to bring about any meaningful change. As the saying goes: “Zameen jumbad, Zamaan junbad, na jumbad Hazrat-e-Jumman!”—everything else has shifted and evolved except the one who actually needed to.

Union Minister Kiren Rijiju attributed the corruption and inefficiency in Waqf Boards as the primary reason behind the recent reforms — which, in my view, are more of a ‘deform’ than reform. The business of exploitation continues unchecked, marked by actions that go beyond legal bounds and by the neglect of responsibilities clearly outlined by law. These practices have only accelerated, especially after the amendments that transfer powers to the District Collectors and introduce a Central Portal for property registration. Meanwhile, the community — led by ineffective and symbolic leadership — remains largely unaware of the day-to-day dealings that unfold within the shadowy, dark, and dank corridors of the Waqf Boards.

Here are some key figures to illustrate the goings on: The total number of Waqf immovable properties stands at 872,985. Out of which, Information is unavailable for 436,356 properties, and Management not entered for 414,051 properties. Will describe the role of the Waqf Board later on.

This data is visible on the homepage of the Waqf portal (wamsi.nic.in). A closer look into the entries for various states and union territories reveals even more disturbing details: (a) Incomplete information regarding the area of many properties. (b) Numerous entries mysteriously marked as “to be deleted” without explanation. (c) Missing income records for several years across different Waqf Boards and (d) Thousands of properties under Waqf Board management report zero income or have not filed returns — with Maharashtra alone accounting for over 3,000 such cases.

Shockingly, this situation has persisted for the last 10-12 years, with no visible effort at reform, correction, or transparency, though figures have increased as a result of progress in data entry.

I have consistently raised these concerns through social media, Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, Jamaat-e-Islami Hind, and various other platforms — but the response has largely been passive, as if speaking to an audience half-asleep. Still, a few of us remain determined. Like those who go about waking people for Sehri during Ramadan, we do our job to awake and alert — regardless of who wakes up or chooses to fast. Or as a meherban put it: we keep on calling for prayers regardless.

The government claims that the Waqf Act 2025 has been introduced for the welfare of Muslims. If that is the case, where does the problem lie? In your view, how and why could this Act pose a threat to the interests of the Muslim community?

The Waqf (no longer Waqf in the true definitional sense) Amendment Act 2025 is not a reform—it’s a deformation. It seeks to eliminate a vast number of Waqf properties that have been under encroachment for over 12 years without any legal challenge. It removes the overriding effect of Waqf Act provisions by making local acts like the DDA Act provisions override instead. It shields encroachers by converting cognisable offences into non-cognisable ones and reducing penalties— effectively incentivising violations.

The amending Act empowers the general public to contest the Waqf status of properties through the office of the Collector, who is not bound by any timeline for inquiries. Meanwhile, all Waqf-related operations are suspended until such inquiries are completed. It also halts the creation of new Waqf properties by introducing a “five years practicing Muslim” requirement. Furthermore, it allows for the confiscation of properties dedicated to Waqf by non-Muslims and dismantles “Waqf by user” claims, slicing off a big chunk of properties like mosques and graveyards etc, where the sanad or waqf namas are not available.

Alarmingly, the amendments permit the inclusion of nominated non-Muslims—undoubtedly figures like Vishnu Jain and Ashwani Upadhyaya, who are actively pushing a patently false narrative—into the Waqf discourse, under the guise of “reform” and supposed support for the Muslim poor and Pasmanda communities.

The matter is sub judice, so we must wait and see.

Even in the worst-case scenario—where only about 30% of Waqf properties remain—we must adopt a demanding and assertive approach vis-a-vis the Waqf Boards. These boards must be held accountable for protecting, reclaiming, and developing these remaining properties, and for ensuring that the income generated is properly directed to the intended beneficiaries.

This requires sustained and organized pressure on boards that have, until now, been handled with undue leniency/undue uncalled-for respect. We must raise large-scale, systemic questions, involve both state and central vigilance authorities, and pursue writs of mandamus/quite warranto, etc, in the High Courts and Supreme Court. (Notably, Senior Advocate Rauf Rahim’s writ petition on the issue of the non-conduct of Waqf surveys is still pending before the Supreme Court since 2019.)

All of this can be achieved through campaigns in Masjidful (similar to the recent BATTIGUL) movement and by engaging Muslim and liberal legislators, as well as other government appointees. The foremost question that must be raised is: Why have state governments, which exercise control over their respective Waqf Boards, ignored the provision of Section 98 of the Waqf Act 1995, which mandates the submission of annual Waqf reports before the State Assemblies?

The equally relevant question regarding the institution under Section 4 of the Waqf Act, 1995, may now be considered somewhat redundant after the amendment. However, we must still await the Court’s order on the matter.

The Waqf Boards are legally bound to: (1) Register all Waqf properties located within the administrative jurisdiction of the state or union territory. (2) Ensure that the income from these properties, if any, is used exclusively for the specified and approved objectives of the relevant Waqf. (3) Develop properties that are capable of development under the provisions of Section 32 (4, 5, & 6) of the Waqf Act. (4) Pay salaries to Pesh Imams and Muazzins as mandated by the Honorable Supreme Court in its 1993 judgment in the Ulema Council writ case, and (5) Cover all their establishment expenses from their own income (specifically, the share of income from the Waqf properties under their jurisdiction).

None of these obligations have been addressed by either the Waqf Boards or the respective governments. Moreover, the Central Waqf Council, which serves as an advisor to the Union Government on Waqf matters and holds the authority to demand reports (such as annual reports and audits) and issue directives to the Waqf Boards, has failed entirely in fulfilling its designated responsibilities.

As stated earlier, the general public’s approach has been equally—if not more—irresponsible, despite the fact that the ‘interested person’ provision under the law empowers them to act. The government’s attitude prior to 08 August 2025, or whenever it decided to initiate so-called ‘reforms’, can best be described by the fatalistic mindset: “Kal ke marte, aaj mar jao.” (Why wait for tomorrow – die today.)

If the Waqf Boards fail to register Awqaaf and their properties falling within the jurisdiction of their respective States or Union Territories, how can they possibly fulfill the objectives outlined above? Unregistered properties are left vulnerable to illegal occupation, unauthorized sales, and usage for purposes other than those specified.

Even registered properties remain at risk of encroachment or unlawful transactions—particularly when mutawallies fail to submit income details or when the property is not developed as mandated under Section 32 (4, 5, and 6) of the Waqf Act.

If no survey is conducted by the State or Union Territory under Sections 4, 5, and 6 of the Waqf Act, and no annual report on Waqf affairs is presented before the State Assembly, the outcome will be no different from what Mr. Rijiju described in Parliament: “corruption and inefficiency.”

Foregoing narration of work not done, duties legal obligations ignored should now serve as a guiding light to our approach for ground-level actual Reforms.

In your opinion, what steps should Muslims, particularly the youth, take in response to the current situation?

It must be strongly emphasized to the public at large, especially the youth within the community, that continued indifference will result in the loss of their ancestral legacy (Miraas)—a legacy with significant potential to generate revenue through development and optimized income, which could support vital welfare initiatives.

The youth—or anyone with youthful energy—can play a critical role, not only by monitoring existing Awqaaf and how their income is being utilized, but also by mobilizing and uniting beneficiaries to collectively hold non-performing or problematic Waqf Board members accountable.

To address and rectify a situation that has gone terribly wrong, it is essential that the educated members of the public (the readers) understand the basics. It bears repeating that Waqf Boards are not just supervisory bodies—they are also responsible for the protection, development, and proper utilization of Waqf income in accordance with its specified objectives.

Hope it serves the purpose .مشکور و ممنون

Great thoughts!